Gabriel Woodson, enslaved Navajo person, in the San Luis Valley (circa 1880). Juan Carson, enslaved Navajo youth of Kit Carson and his wife, Josepha appears in back. Per Cynthia S. Becker and P. David Smith in The Life & Times of Lafayette Head “Kit Carson’s wife, Josepha, traded the Utes a horse for a boy called ‘Juan,’ who was going to be killed. Everyone agreed Juan was treated the same as her own children. Juan lived with the Carson family until he was grown and found a wife.” (Page 194.)

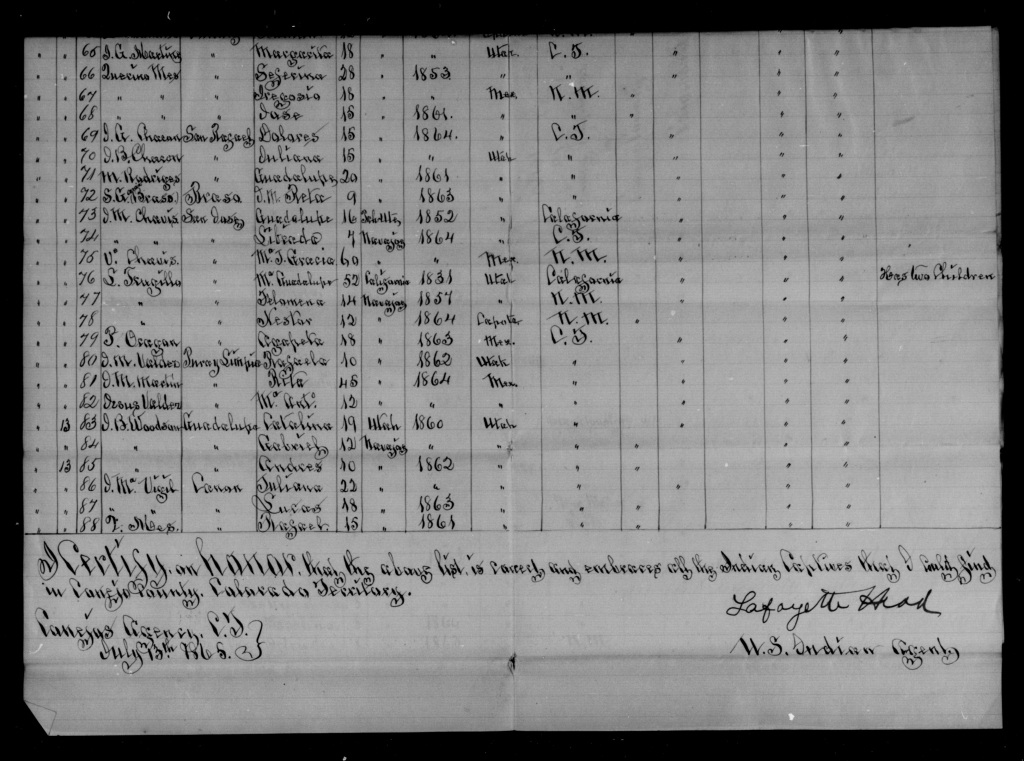

On June 28, 1865, President Andrew Johnson had directed every Indian Agent in the Southwest to conduct a survey to determine persons holding Native American captives as slaves, although they were not at this time asked to free Indian slaves. When Lafe submitted his list of Indian captives to Colorado Governor John Evan on July 17, 1865, he recorded over 160 names in Costilla and Conejos Counties. His full transmittal letter reads as follows:

In the company of E.R. Harris, U.S. Marshal, I called upon all those persons that hold Indian captives in Costilla and Conejos Counties and interrogated the Indians themselves, and their replies to my inquiries, you will please find in the accompanying lists which embrace within my knowledge every Indian Captive in these two counties, and to the credit of the citizens here I would add, that they all manifested a prompt willingness on their part to give up said Captives, whenever called upon to do so, and in view of the facts, I would most respectfully recommend, that all the Navajo Captives here be returned to their Reservation in New Mexico. Also the few Ute Indians residing in private families here, it is generally understood that they are there with the consent of their parents or friends, and enjoy the full privilege of returning to their people whenever they have the inclination or disposition to do so. Very many of these Ute children are orphans, are therefore homeless and perhaps under these circumstances, their condition would not be so much benefited by your order. Yet if your order is imperative, and you are instructing me to have them all removed, I will promptly do so.

I have notified all the people here, that in the future, no more Captives are to be purchased or sold as I shall immediately arrest both parties caught in the transaction. This step, I think, will at once put an end to this most barbaric and inhuman practice, which has been in existence with the Mexicans for generations.

There are captives here who know not their own parents; nor can be speak their mother tongue, and who recognize no (sic) one but those who rescued them from the Merciless (sic) Captors. What are we to do with these? I would here add that I have not incorporated in the accompanying lists the large number of Captives that have legally married in the two Counties.

I shall wait for further orders from you in regard to their removal. Please also instruct me what course I shall pursue in the premisis (sic) in regard to those who are not willing to return to their people.

A number of well-known men in the San Luis Valley were on Lafe’s list of slave owners, and Kit Carson was said to have three such captives.

Governor Evans promptly forwarded Lafe’s July 17list of captives to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington with the good suggestion (Probably influenced by Lafe’s transmittal letter) that those “slaves” who did not want to return home not be forced to leave their adopted families, and he considered the project closed. Governor Evans, however, was not aware of one major problem with Lafe’s list – that it did not include any of the Indian children living on Lafe’s home or living with other families in the Town of Conejos. Lafe would later submit a second list that would include himself and other Conejos residents that were slaveholders.

The Life & Times of Lafayette Head by Cynthia Becker and P. David Smith, Pages 190-191.

Millions of Indigenous people lived in North America before European colonial powers invaded. Along with an insatiable desire for free labor to cut sugarcane and to mine gold in the Caribbean and later to mine silver in New Spain (Mexico), Europeans brought a system of slavery that significantly differed from the system of enslavement practiced by Native nations which both pre and postdated African slavery. European concepts of bondage transformed the way Native nations interacted with each other, resulted in the enslavement and death of millions of Indigenous people, and sparked widespread resistance by Native nations in North and South America against colonizing powers (primarily Portugal, France, Britain, the Netherlands and Spain).

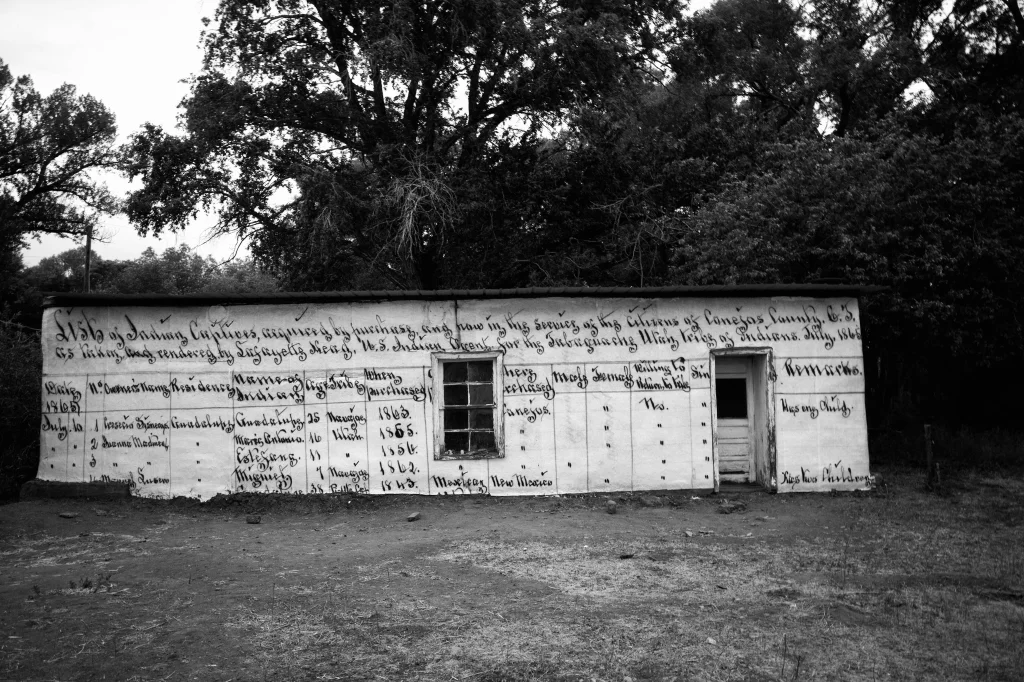

Nestled at the foot of Mount Blana, a mountain sacred to local tribes and one of four Sacred Mountains to the Diné (Navajo), Fort Garland was constructed by the U.S. Army in July 1858 to protect settlers from tribes whose land the settlers took. The fort was abandoned in 1883 after confining the tribes defending their land to reservations in Utah, Arizona and Colorado.

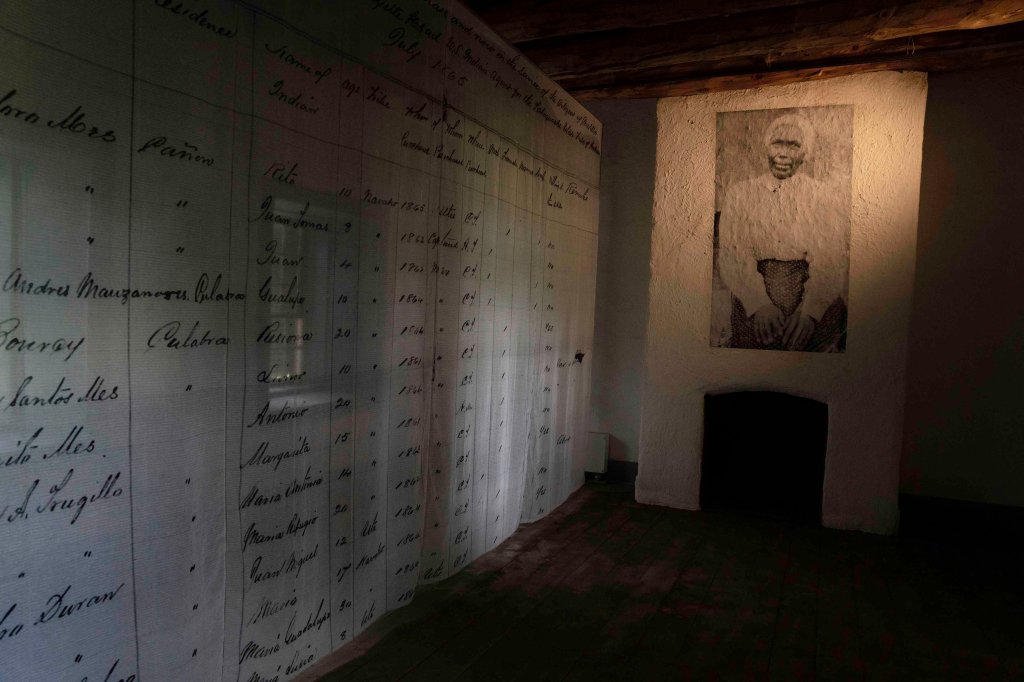

Wanting to engage the local community in difficult conversations about Native enslavement in the San Luis Valley Fort Garland Museum held a series of Zoom conversations encouraging participants to share family stories and photos of distant enslaved family members. One Latino participant shared how DNA testing is changing awareness of Native ancestry for many people in the valley. Inspired by an invitation from Fort Garland Museum to install work related to Native enslavement in the San Luis Valley I used this opportunity to begin learning more of this obscured history. As someone who has spent the past 34 years living and working with with the Diné on the Colorado Plateau in northern Arizona and as an African-American this history intrigues me. Many Diné friends shared stories with me over the years of family oral histories that involve distant relatives being captured in battle with other tribes and being held captive. Learning of Native enslavement wasn’t new information for me. However, the motivations, extent and consequences of it were.

Thank you Drew Ludwig, Esther Belin, Ronald Rael, Estevan Rael – Galvez, Eric Carpio, Dawn DiPrince, Delia Charley, the Fort Garland Museum staff, Richard Saxton and the good people of M12 for helping to make this work possible. It takes a village to prevent truth decay.

Unsilenced is part of the Landlines Initiative organized by M12 STUDIO. Since 2018, the Landlines Initiative has connected new art installations and cultural work throughout Colorado’s rural San Luis Valley. This work is supported by awards from Colorado’s Arts and Society, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts.